Welcome to “The Pope’s Comics,” our regular column by award-winning novelist, poet, and Comic Watch contributor Bethany Pope! Bethany brings a wealth of knowledge on literature, LGBTQIA+ issues history, gender, comics, and so much more. We sincerely hope you enjoy!

In honor of the long-awaited return of Brian Vaughan and Fiona Staples’ immaculate Saga series, I’m going to spend the next few weeks exploring different themes that surface within that story. It’s rare for a series to explore, so thoroughly, such a wide variety of stories, characters and themes without sacrificing either consistency or narrative heft, but Saga has thus far executed the juggling act without faltering.

Today, I’m examining one of the many births that occur within this series. There have been several, so far, and I’ll examine them later, but since the birth of Hazel was so groundbreaking in its own right (as well as being the incident which ignited the series) it deserves an essay of its own. I’ve divided this essay into three sections: Birth, Mother, and Father. This is, obviously, a very heteronormative structure. I’ll examine non-nuclear and Queer family structures, as they appear within the text, at a later date.

I’d also like to issue a content warning, at this point, for the discussion of violence, childbirth, and child endangerment.

Birth

Hazel’s birth was revolutionary, in several ways, both within the medium of comics and in pop-culture and literary fiction. The opening pages of the series are centered around the image of Alana, spreadeagled on the top of a table, as she worries about ‘shitting’ herself whilst riding her contractions. The images of baby Hazel, when she finally emerges, are of an inchoate, squalling, bloody lump — with the placenta still attached and dangling, red and glistening, from the curled, pearlescent umbilicus. This is a shockingly realistic image. If you’ve ever had or borne a child (regardless of gender. Trans parents and adoptive parents exist) this scene was familiar rather than unsettling. And it wasn’t meant to be shocking. Staples was as careful to capture the adoring looks of the parents as they regarded their jellylike spawn as Vaughan was in ensuring that the narration emphasized that love. Newborn babies aren’t cute. They’re red, veiny, covered in peculiar hair and thick white wax. But most (certainly not all) parents look at them with powerful, terrifying love, tremendous fear, and something akin to adoration. Marko’s and Alana’s responses were certainly familiar to me. I had a rather traumatic birth experience (I was technically dead for three minutes) and my last thought as consciousness sank away from me (and my first thought, as I regained it) was that I would do literally anything to protect the gooey lump of proto-human that I’d somehow managed to produce. I’d kill anything, conquer anything, climb any mountain to keep that kid alive. It was incredibly refreshing to see both aspects of the situation (the blood, the shit, and the love) so perfectly and succinctly captured.

Mother

It’s amazing how frequently mother’s are depicted, within fiction, as instantly losing all vestiges of their personalities the second they push a baby out. They cease to be people almost as frequently as they are swiftly killed off. Alana doesn’t have this problem. She’s self aware, driven by her own motivations, and although her priorities shift (in this instance, from her own survival to ensuring the life and happiness of her spouse and daughter) she is not subsumed in motherhood. Again, I’m only focusing on the very early stages of her parenthood, before the wrestling and her dabblings with drug abuse. She talks about her nipples hurting, about Hazel spitting up in her mouth. She argues with her husband about how they will introduce their cultures to their child. She mentions her daughter’s uncanny ability (shared by most infants) to sleep through a tremendous amount of noise only to be awakened at the most inopportune moment by something seemingly minor. But she does so as Alana. Everything she says is delivered through the lens and focus of her personality. It’s shocking (and a little bit disheartening) how rarely that’s true, in any media.

Father

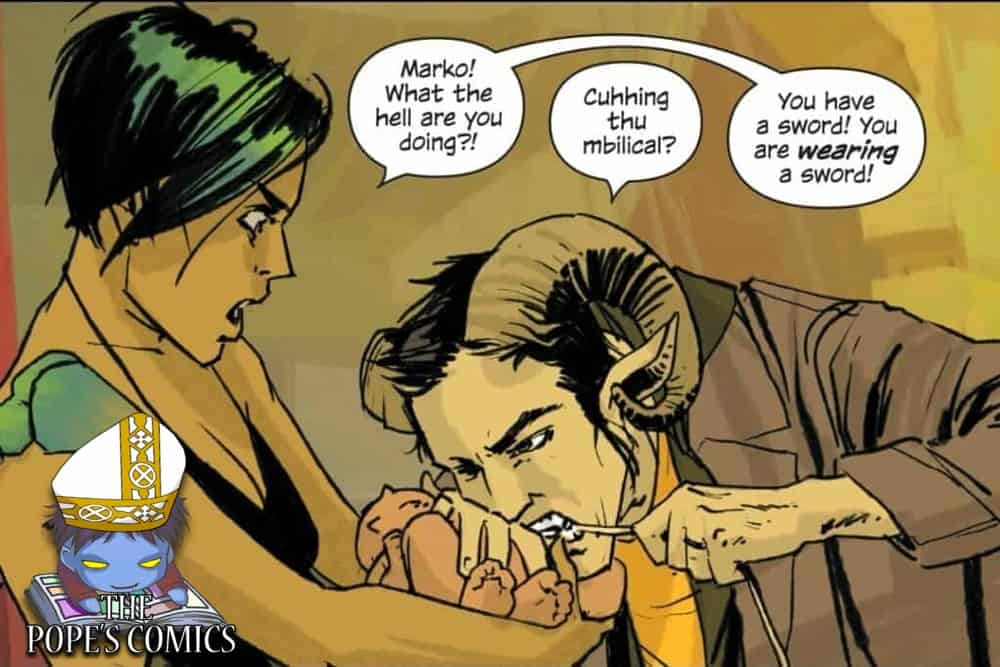

Marko’s role also breaks several stereotypes. It’s true that the role of ‘sensitive male’ has been played (and, usually, mocked) before, but it’s rare for a father to be depicted as forcing himself to be considered and delicate in his actions as a response to his struggle with PTSD. The fact that Marko is shown to be largely successful in his goal of nonviolence, at this stage, even when doing so paints him as slightly ridiculous (as when he bit off his daughter’s umbilical cord rather than cutting it with a sword) is rather revolutionary. There’s a devastatingly low bar for fathers in fiction, and the fact that Marko not only delivered his child, but responded to the blood and trauma of birth with wonder and joy catapulted him as far above that small, sad goal as Wreath hovers above Landfall.

It’s sad that the depiction of healthy straight, cis parental relationships are so rare, both within comics and in fiction as a whole. It’s sad that such a realistic depiction of birth (outside of the larger circumstances) is so revolutionary. That this naturalistic, humanistic, approach launched a sci-fi/fantasy series is nothing short of remarkable.

Poet, novelist, fencer, pirate, Za-Za, and Comic Watch regular contributor Bethany Pope lives in China. They also hold an MA and PhD in creative writing. Their latest novel, The Hungry and the Lost, was released December 1, 2021 from Parthian Books. You can follow them on Twitter at @theMasqueWriter.