Welcome to the inaugural edition of “The Pope’s Comics,” our new regular column by award-winning novelist, poet, and Comic Watch contributor Bethany Pope! Bethany brings a wealth of knowledge on literature, LGBTQIA+ issues history, gender, comics, and so much more. We sincerely hope you enjoy!

Content warning: This column treats the subject of murder, rape, and sexual assault in comics. Many, if not most, of the books I’m going to be analyzing have no content warnings whatsoever, though they absolutely merited them. This essay will likely be triggering to some people, and upsetting for most, even though the purpose is a deconstruction of the trope. Proceed with caution.

Twenty-two years ago, Gail Simone launched a website which listed the names of the female characters who were killed and depowered in comics — usually by male writers, and almost always in order to further the development of male characters. The website (and the list) still exists, and I would recommend giving it a Google. It’s called ‘Women In Refrigerators’.

Since then, ‘Refrigerating’ has become a term for what happens when a female character is transformed into the catalyst for a plot which furthers a man’s story. Almost every western comics property has fallen into this trope at one point or another, and although it is, shall we say, disheartening to examine every instance of this trope, such analysis is necessary if we intend, as readers and writers, to demand better from the art.

Simone’s website provided little analysis — it’s just a list of character names, followed by the abuses they’ve suffered — but it honestly doesn’t need to be more detailed to be effective. When you look at a stack of names and read, ‘dead, dead, dead, depowered, lobotomized, raped, dead, dead, dead’ it has a profound effect on a person — especially if you’ve been raped or assaulted yourself.

The fact that female and LGBTQ+ characters are so easily thrown away or murdered for the sake of a (straight male character’s) story reflects the fact that the same things happen to us in real life — with astonishing frequency. One in four women will be raped or sexually assaulted in their lifetimes. Trans people, especially trans women of color, and non-binary people, experience a ridiculously high risk of being flat out murdered for the sin of existing as themselves.

This essay aims to expand on the analysis of what happens to women and members of the LGBTQ community when they’re written by people who haven’t dealt with their internalized misogyny. I’m also going to touch on the way that straight cis male characters are treated when they’re raped, because it’s there that you see that misogyny bubbling to the surface, since the men are usually ‘feminized’ and mocked during their rape, and indeed that feminization is seen as contributing to their humiliation.

I’ve divided this essay into six sections, each dealing with the ways that Women and other Non-straight, Non-Male characters are tortured, raped, or otherwise eliminated within the texts. I will explore the whys and wherefores, and provide a little bit of theoretical analysis for each group as I get to it.

Please keep in mind that this is not a comprehensive list. For one thing, I only touch on race in a few instances, but black and other POC characters are uniformly abused more frequently in the text than white characters. That’s important to remember as you’re reading. I could write a literal thesis on this subject and there would still be places to explore within it. Think of this, instead, as an introduction.

And remember, once again, I am dealing with some pretty graphic subject matter. There is a huge Content Warning for this essay.

1.Rape

Rape as a woman’s ‘dark’ backstory.

Many female characters are raped, either as a means of breaking them, providing motivation for another (usually male) character to become a ‘better’ person, or as a means of making a fictional world seem more gritty or ‘realistic’ to an audience that is presumed to never have encountered such things. In this section, I’m going to examine some of the reasons behind the abuse of specifically female characters. I’ll examine a few examples of characters that have been raped, and we’ll see how these assaults have been used either to affect the characters themselves or else to motivate the men around them.

Carol Danvers: Before being depowered by Rogue, Carol was mind controlled, kidnapped, and forcibly impregnated by a third-rate villain who hasn’t really been heard of again since. Carol’s rape (in Avengers #200) was initially brushed off, both by the writer and by her fellow characters, because if a woman doesn’t scream or seem to fight, it’s not really rape, I guess?

This storyline can be interpreted, and therefore partially reclaimed, as an allegory for date rape, but it’s really difficult to read the issue and watch Beast and Captain America making jokes about the fact that Ms. Marvel was abducted and forcibly impregnated.

Jessica Jones: At the time of her rape, she was an almost forgotten character. Her extended imprisonment and rapes at the hands of The Purple Man were written in order to make her more ‘interesting’ and ‘edgy.’ Despite art which depicted her abuse in what was intended to be a titillating way, and the fact that the only way a male writer could think of to treat trauma was by showing her rapes, this series, and the follow up Purple Daughter, did a good job of exploring the after effects of a long imprisonment/multiple assaults.

Rape as a Bridge Too Far

Sometimes, the rape of a female character is used as a means of signaling that a male character is beyond redemption. This is a problem because, once again, female pain is being used to reflect the story of the man who is raping her. Contextualized this way, her pain is nothing more than a side effect of the man’s more important story. Here are two examples of such handling.

Lourdes Chantel: This character recently reappeared in Marauders #22. She’s been presumed dead for years, but Gerry Duggan recently revived her as a means of proving that Sebastian Shaw is a character who deserves the punishment that’s soon to be coming to him. She went from being a character with agency and power (in Claremont’s hands she was a high-ranking member of the infamous Hellfire Club) to the beaten, raped victim of Shaw’s appetites. Not only did this retcon remove any agency the character might have had, even as a villain, but it flattened her into both a tool for the rehabilitation of one character and the damnation of another.

Barbara Gordon: While Barbara’s rape in The Killing Joke is strongly implied, rather than baldly stated, it is shown in the sense that we get a mosaic of her crating ‘sexy’ facial expressions while lying in a puddle of blood. Prior to this story, Barbara had been enjoying a career as a crime fighter. It’s true that, after her paralysis, she eventually became one of the few disabled superheroes, but that was after the character endured a long stretch in Refrigerator Limbo. This character was raped solely to prove that the Joker was a monster while giving motivation for Batman to hunt him down. The story was, after all, focused on the Joker attempting to break her father, Commissioner Gordon, by giving him ‘one bad day’. Rape, in this story, was depicted as a sin against property: the Joker raped Barbara (property) in order to hurt Gordon (her father/owner). Barbara was a plot in this story. Not a person.

Rape as a Redemptive Force

Occasionally, rape is used as a means of ‘redeeming’ a female character. We see this, as I mentioned above, with Lourdes Chantel. Her rape becomes the catalyst for Emma Frost (a former villain) to come to the light. This plot is often intended to show that an evil person can be redeemed through a change in circumstance (in this case witnessing the pain of a friend) but it’s actually yet another means of removing agency from women.

In this dichotomy, ‘bad’ women act; ‘good’ women are acted upon. In circumstances where the rape is perpetrated or assisted by a woman, we see something a little more complex, but still equally disturbing.

Emma Frost: This character, once the top ranking woman of The Hellfire Club, acting from her own motives, was retconned into being the drug-addled pawn of the man who really ran the show. She didn’t want to be evil, you see. She had no choice. She was forced to be evil as a side effect of her captivity.

This tendency of writers to bind women with drugs, so that they will do as they’re told, is incredibly frustrating. It’s intended to be an excuse, so that we (readers) can forgive the characters for doing things like, oh, taking over the body of a black woman and allowing their boyfriend to have sex with it. In Uncanny X-Men #152, Emma Frost steals Storm’s body and, well, you can see the picture.

Here we have an older, rich, white woman appropriating the body of a black immigrant and sexualizing it. This is rape of a kind that should be very recognizable to modern readers. This is an act of evil, and no question about it. But it’s also an action that she (Frost) chose.

If Emma only did this thing because she was being mind controlled by Shaw, we readers receive two messages. First, this says that women can only act in ways that are evil. Women cannot both have agency and be good. It also says that the only way a female villain can be redeemed is if she was never in control of her actions in the first place.

Male villains get to be redeemed because they decide that they were wrong and they decide that they have to change. Female characters are redeemed when they are forced to change, either by circumstances or else via the auspices of the men in their lives.

Women who fall (or are pushed) into this trope can only be ‘good’ when they have the power to choose between good and evil, between action and inaction, removed from them.

Rape as a Means of Fostering ‘Realism’

Readers will often excuse the use of rape in a story as being a means of making a fictional world more ‘realistic’. Since rape is so common in our world, they reason, shouldn’t it also be common in fiction? This is presented as a valid argument, without considering that the presence of rape in fiction (the constant, oxidizing rain of trauma) serves to normalize it for readers. After all, if it’s inevitable, why should we have to question it? Why should we confront toxic masculinity if women are going to be raped anyway?

Notice the passive voice, there? When we think of woman as raped, or getting raped, we need to ask ‘by whom?’ Who is performing the action?

The presence (constant and eroding) of one and only one depiction of rape also tends to hide other varieties from view. If your definition of rape begins and ends with a violent assault, forced by a stranger, leaving behind a body that’s bloody and covered in bruises, you miss a lot of real trauma.

Rape by coercion, rape by a friend, the rapes in which one party berates the other into giving in using nothing but a stream of words. These rapes aren’t shown, and you know why that’s so? Because those rapes aren’t titillating. They aren’t visually appealing. They don’t look ‘sexy’ when drawn.

In real life, men rape people because they want to. In fiction, writers and artists put rapes on paper because they want to. That’s realism, I suppose. Of a kind.

Rape as a substitute for Plot

This is the last little bit of the section on rape, before we move on to the cheerful fields of mutilation. I’m spending a lot of time on the rape of women by men, because that’s the category that the vast majority of rapes in comics fall under. But I’ll explore other varieties of rape shortly.

For now, let’s look at rape as a means of furthering the story of a (usually male) protagonist. This overlaps, in a lot of ways, with using the rape of a woman to show that a character is beyond redemption, but there are some differences. For one thing, sometimes the character whose plot is being advanced is the person who was raped.

Magik: Illyana Rasputin is a complex character. Her whole life to date is rich with examples supporting my theme, but I’m going to stick to her early appearances in the X-Men lore. Magik is the sister of Colossus and was originally a child in his care. She was kidnapped to a hell-like dimension called Limbo and she was raised by the lord of the realm, a demon (whose form resembles a middle-aged man) who taught her magic and pretty explicitly raped her off camera.

These rapes, which were framed (problematically) as the loss of her innocence, were the driving force for decades of stories. She had many adventures, as a teenager and as an adult, and most of them dealt with the loss of her ‘humanity’.

The analogy was clear: rape makes people monstrous. Certainly, in reality and on the page, it isolates you, makes you other, and in many ways Magik’s story serves as an accurate reflection of how the world treats rape survivors. Certainly I (a non-binary rape survivor) felt a great deal of sympathy for the girl who was demonized and insulted by her religious classmate. I empathized with the character’s thwarted desire to be normal again, to be her brother’s ‘little snowflake’ after feeling as though something essential had been forcibly stolen from her.

In many ways, Magik is an example of a successful depiction of the emotional aftermath of rape. This is explicitly because the rape is firmly established as part of her story. It sets her up for future adventures. It gives her her power — literally in the presence of the Soul Sword that she fashions from her trauma, and figuratively in the attitude she wears to face the world. Claremont did a brilliant job with this character.

Unity Kincaid: In Neil Gaiman’s brilliant Sandman series, Unity plays the role of Fifth Business. In the world of opera, Fifth Business is the character who makes things happen. It’s the Priest carrying news of the end of the war, or the King who comes back just in time to stave off the execution. It’s not a big role, but it is important. It is a pity that Unity plays it by being raped.

Her rape happens while she is unconscious (doubly bereft of agency) and she gives birth to a child who, for a time, threatens to destroy the Dreaming. Her rape serves to propel the story of both Dream and his sibling Desire. More on why it’s problematic for a non-binary person to be depicted as a rapist in a bit.

It’s also disturbing that her rape, and the forward momentum it gives the plot, happen while she is almost literally dead to the world, in deep sleep.

Barbara Gordon: As you can see, many of these rapes check more than one box at a time. This is not because I have so few rapes to choose from, but rather, it’s here as a way of showing the many effects that these depictions have on readers. Barbara’s rape motivated Batman in the same instant that it damned Joker. Indeed, it served every purpose except giving the victim an inner life or personality.

In comics, women are depicted as being the perpetrators of rapes far more frequently than they are in real life. When a woman is depicted as a rapist (more on this, in a minute) the process is not shown to be as traumatic as it often really is for male survivors. The intended effect is often one of titillation, as though it must be sexy for a man to be raped by a woman, because no woman could really overpower and victimize a man. The BDSM flavor often given to these scenes is disturbing, not least because it sends a horrible message to men who are rape survivors. I suppose the idea is that they should just lay back and enjoy their own abuse. You can see how this would fail to be helpful.

2. Straight Male Victims

When straight men are raped by cis women in comics, the effect is either underplayed, hypersexualized, or else presented as a joke. One aspect of toxic masculinity is that cis, straight men are supposed to exist in a state of constant, exaggerated sexual arousal. These fictional men can consistently be distracted by a flash of boob, or a sliver of glute. They are written to be always ready for action, in every sense, and when they are raped, they soon become consenting accomplices to their own abuse.

It’s interesting that most of the examples of the rape of straight, cis men came from DC. Perhaps the publisher’s reputation for ‘grittiness’ carries some of the blame.

I’m focusing on three of the more high-profile rapes. This list is not by any means comprehensive, and I’m excluding Y: The Last Man because if I start talking about that I’ll never stop.

Batman: Talia Al’Ghul drugged Bruce so that she could force him into sex and have his child. So, we have forced insemination, date rape, and rape by deception all in one fun package.

This rape is the one that is dismissed by fans the most often out of all the assaults that I’ve covered in this article. And it’s dismissed for the same reasons that a lot of male on female rapes are: Bruce and Talia later have consensual sex. As though, somehow, saying yes three times means that you can never say no again.

Olivier Queen: The villain Shado beats Olly until he is hallucinating and then engages in rape by deception by pretending to be his longtime partner, Black Canary. You might recognize this move, in slightly altered form, from the 80’s film Animal House. Rape by deception is when the perpetrator (not ‘partner’) tricks their victim into engaging in sexual activity by pretending to be someone else. In the real world, doing this will land you jail time. In comics-world, when it’s brought about by a woman and the victim is a man, it’s depicted as ‘sexy’.

Nightwing: When Dick was exhausted from a fight, Tarantula (a female hero) used his weakened state to force herself on him. This action gets two pages of art, and we see Nightwing’s protests, as well as an explicit (if shadowed) shot of the rape itself. Again, this rape is depicted as a ‘sexy’ event. All of the usual signifiers of hot Bat love are present: the night, the shadows, her smile, the curve of her thigh. We are supposed to forget that we are witnessing a rape.

3. Refrigerating LGBTQ+

The Rape of a Straight Person by a Member of the LGBTQ+ Community

This rundown will be considerably shorter than the above diatribes on heterosexual female on male and male on female rapes. This is because most rapes in comics feature a cis man victimizing a cis woman. Still, there’s a lot to cover here, and none of it is fun.

As hinted in the previous section the rape of a straight person by a member of the LGBTQ community is far rarer than the reverse (‘conversion’ rapes, wherein a straight person, or community, attempts to ‘cure’ a queer person by raping them happen. Queer people don’t try to rape straight guys or gals into queerness) and yet they show up frequently in fiction, especially within the medium of comics. I’m only going to cover a few examples, here.

Mr. Hyde: Alan Moore has this character rape The Invisible Man, in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, as a form of vengeance for the rape he committed. This is depicted as a sort of quasi-justice, and it is brutal. This reads as an attempt to say, ‘rape can be good, sometimes’. Readers are meant to empathize with, or at least approve of, the actions of Mr. Hyde and we see it happen, explicitly, over the course of a few panels.

Unity Kincaid: As I mentioned before, Desire of the Endless rapes Unity Kincaid in an effort to destroy Their brother. Unity is viewed, from Their perspective, as a tool, not a person, but that is consistent with Desire’s usual view of people. In this instance, Their manipulation of the people around Them is meant to reflect their particular character, and not an attitude shared by LGBTQ+ people.

The Rape of LGBTQ+ Characters by Straight Characters

LGBTQ+ characters who are raped appear much, much less frequently than cis women, and when it happens it’s usually (disgustingly) played off as a joke. Pansexual Deadpool was raped by a woman, and it’s supposed to be hilarious, because in popular culture men are supposed to want sex all the time and if they say no, why, you can just force them to do it. This is the other side of the coin to showing the rape of a straight female as a defining (destroying) event. The rape of a man, queer or otherwise, is reduced to comedy.

I’m going to explore this theme again a little further down. For now, we’ll look at another method of eliminating a character from regular rotation.

4. Depowering

Depowering as Punishment

Depowering is a means of shoving a troublesome female or LGBTQ Character deep into the freezer. Male characters tend to come back from it. Female and queer characters tend to remain depowered. The reasons that it happens this way share a lot of overlap with the sections on Rape that we covered above, so I’m not going to repeat myself there. You can use your imagination to fill in the blanks.

Often, a woman or queer character is depowered as a form of ‘punishment’, either for being queer or for some perceived flaw in their character. Moondragon, one of the few early lesbian characters, was fitted with a power-dampening headband soon after coming out.

The gay X-Man Northstar was also depowered very soon after being confirmed as gay in Alpha Flight.

Betsy Braddock, a bisexual woman (with a horrific history of race-bending and appropriation) was mutilated by the male villian Mojo. He had her eyes removed. She was later depowered as a means of clearing her from the X-Men roster.

Depowering as Plot

At other times, Depowering is used to further the plot of a story. Occasionally, this happens in the same spirit as rape: the trauma and loss of control a woman or LGBTQ Character is forced to endure furthers the plot for someone else. Luckily, we also see instances in which a character is forcibly depowered and that loss is framed as an opportunity for growth.

When Storm lost her powers (at the hands of her boyfriend, transforming this instance into a variety of rape) the focus on her development as a character strengthened. The story was focused on how this mutilation affected her, not anyone else, so we saw her grow into a more confident hero and a more effective leader instead of losing her to the character limbo that’s claimed so many others.

It’s worth remembering that one proposed end for Claremont’s game-changing “Dark Phoenix Saga” would have ‘allowed’ Phoenix (then believed to be Jean Grey) to survive — at the cost of her powers. The Shi’ar would have lobotomized her.

Like Storm, Wonder Woman’s depowering was intended to lead to growth for the character. Unfortunately, the effect was considerably more problematic. Not only does Diana (a trained warrior) suddenly lose the ability to fight, she has to retrain in Kung Fu — a decision which leads to a series steeped in racism as well as misogyny.

Hey. At least she wasn’t raped.

5. Death

In this section, I’m going to talk about the kinds of stories which, most frequently, reduce women to plot. I’ll start by exploring the death which started this all. Although this trope has, if anything, increased in frequency, I’m going to use examples from the 1980’s and 1990’s because they are more familiar to audiences.

Woman in Refrigerator

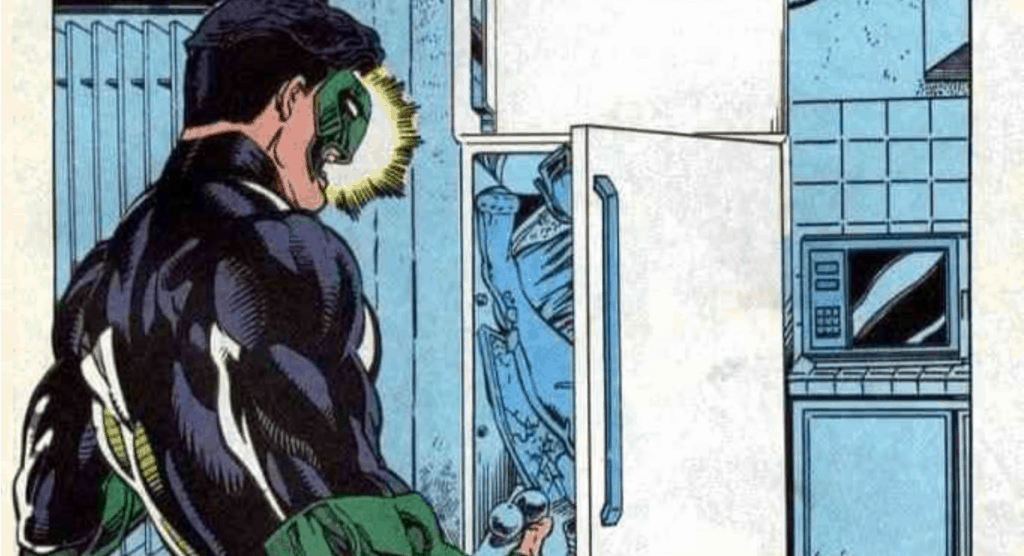

Alexandra DeWitt: In Green Lantern (vol. 2) #54, hero Kyle Rayner comes home to discover that his girlfriend, Alexandra, has been murdered, dismembered, and shoved into his refrigerator. Gail Simone used this death to title her series, and it’s easy to see why. The entire emotional effect, all our sympathy, is meant to be directed towards how the man feels. We aren’t meant to imagine how it would feel to be killed. We are supposed to sympathize with how it would feel to uncover the body.

Like the rape and mutilation of Barbara Gordon, this murder is depicted as a sin against property. Alexandra was murdered to send a message to Rayner. She isn’t the point: Rayner’s pain is the point.

If a murder only matters if it hurts a man, then it’s a lesser crime than it should be. It becomes an injury for Rayner, instead of a true death. Alexandra was literally objectified, here. She was transformed, by the alchemy of story, from a person to a corpse.

Candy Southern: Once the love interest for Warren Worthington III, Candy was kidnapped, tortured, and murdered by Cameron Hodge in an effort to discredit X-Factor. This is a rare example of the trope being written by a woman. Louise Simonson is known for her stellar character work, and X-Factor #34 is definitely affecting, but the sole purpose of Candy’s presence in the story is designed to build towards Warren’s reaction. We see her, and experience her death, through the lens of his emotions. Her death exists to lend his character some depth.

There are literally hundreds of examples of this trope to choose from. Once again, I strongly recommend checking out Simone’s website for more.

Go Evil, Then Die

When this happens, women gain great power and then go mad before dying. Often their deaths are seen as ‘deserved.’ This version of the trope is a little bit different from the last because the reader is made to inhabit their perspective for longer periods of time. The aftermath, however, is all on the men. The legacies of both the following stories land squarely on Scott and Alex Summers — indeed, both men are still benefiting from these deaths, thirty and forty years later.

Dark Phoenix: Once again, Claremont did a great job focusing the saga of ‘Jean’s’ sudden power upgrade and growth into a top-tier superhero through her eyes. Readers saw the being who thought of herself as ‘Jean Grey’ (from here on, referred to as such, so that none of us develop continuity headaches) develop from an undervalued accessory to the original X-Men to the central figure in her own story, before succumbing to the temptations great power bestows, committing genocide against a society of broccoli people, and finally being tried for her crimes.

Claremont allowed Jean to express what is in many ways the ultimate agency by choosing to die on her own terms. She said goodbye to Scott Summers and stepped in front of a deadly alien laser. So far, so feminist.

The aftermath of this story reduced her to an accessory to Scott Summers’ grief. His storyline, from that point on, was centered around his feelings for Jean. And she was reduced to the object of his grief; flattened out of personhood.

This problem was doubled two decades later, after Jean was resurrected (more on that, in a minute) and the two were married. When Grant Morrison wrote an end to their marriage and had the ‘real’ Jean reenact “The Dark Phoenix Saga” in miniature before killing her, again. Jean was once again reduced to an object — in this instance one that acted as an impediment to Scott’s love life. Since Grant Morrison is Grant Morrison, there is a direct connection between Jean’s refusal of sex, her stifling of that energy, and her explosion into Phoenix. The clear, albeit unspoken, connection is that she was eliminated for the sin of not putting out.

And I have to say, one non-binary person to another, Morrison really needs to examine his misogyny. Because it comes up a lot. And it’s worse when it comes from one of my people.

Madelyne Pryor: Ah, Maddy. Poor girl. Madelyne was created for the not-at-all problematic purpose of being Scott Summers’ happy ending. Her entire purpose was to be someone whom Scott could love (because she was basically Jean’s twin), marry, and ride off into the sunset with.

She escaped complete objectification by having an extremely distinct personality, a feminist identity, and a career as a pilot.

She and Scott married, Cyclops ‘retired’ from the X-Men, and they quickly had a child.

Instead of a happy ending, editorial mandates dictated the formation of X-Factor and the revelation that Jean was in a chrysalis on the bottom of Jamaica Bay, rather than dead. Scott left Maddy, took the baby, and went back to have adventures with Jean.

At the time, because it was impossible for a ‘hero’ to be a cheater, Maddy was vilified. She became a clone, created to steal Scott’s DNA and give birth to a baby that the mad geneticist Mr. Sinister could manipulate. This led to the Inferno event, Maddy’s ascension into the vicious Goblin Queen, and eventually her death.

Since Claremont was still in control of the character, readers were given great insight into her interior struggles, culminating in a heart wrenching dream-scene in which Jean Grey strips Madelyn of first her clothes, then her features, before finally walking away with her life.

The problem, Maddy’s Fridging, begins with her death.

Post-death, Maddy becomes a plot point. She reemerges every so often, to be either a harpy or an incestuous, sex-hungry tormenter of Summers men, but her character has been utterly erased.

She ceases to be a ‘real girl.’ Even in her most recent appearance, in the current Hellions series, her purpose is to provide angst-fodder for Havok, her former brother-in-law/lover. Unlike the men in her life, she only gets one story: to have creepy sex, be evil, and die horribly.

Bury Your Gays

I included LGBTQ+ people of all genders in this essay because they are often killed and depowered for the same reasons, and in similar ways, as straight cis women. If a gay character also happens to be a cis woman, watch out.

Ultimately, it seems that many (straight, male) creators still see LGBTQ+ characters as existing to serve the same purpose as straight women: a motivation for a male character, the real character, to act.

This section is going to be very unpleasant, even in relation to all the dreck that’s come before. This is because being LGBTQ+ is still viewed, on some level, as something that needs to be punished. And these characters were punished.

Freedom Ring: This was the first Marvel character to come out, and he was brutally murdered within a month of making his announcement.

Moondragon: She was captured by Thanos in Marvel’s Annihilation: Conquest series. Thanos tore her ears off and gave them to her lover Phyla as a threat. She survived this, but was ultimately killed after being transformed into a literal dragon, when she sacrificed herself to save her lover. Because if you have a happy queer couple, one of them has to die. I will not include a picture of the ear incident. Here’s a picture of her as a dragon.

Batwoman: Kate was brought back, after years of limbo, only to be stuffed in the fridge by League of Assassins for the sole purpose of giving Bronze Tiger something to regret.

Northstar: The month he came out, Northstar was murdered, twice, in two different alternate reality stories. He was also originally supposed to die from AIDS, because if he’s a gay man, he has to have aids. They settled for making him go insane instead.

In Civil War: Young Avengers/Runaways, a trans character (one of the few in Marvel) gets her neck broken, Carolina, a lesbian, is kidnapped, gay Hulkling is dissected, his now-husband also got kidnapped, and every single straight character in the series survived intact.

6. Women as ‘Hero’

This last section is going to be very short, primarily because I have been buried in rapes, murders, and gender-based humiliations for the better part of a week while I was getting my sources together and composing this essay. I’m physically and emotionally sick of this. And it needs to stop.

Writers, especially straight cis male writers, but definitely all of us, need to do better. We need to analyze the stories that we’re telling, and we need to understand why we feel compelled to write the plots that we do.

Anyway. One way that writers try to be better about this mess is by taking the exact same tropes and changing genders of the characters. They do this without seeming to realize that the pattern is the problem. The fact that, in these stories, one character gets to be a person and the other becomes an object, is the problem. Changing the genders of the players doesn’t alter the game.

So, if you take the ‘Rape as Redemption’ story that I outlined above and change it, as Gerry Duggan recently did, to feature two women, rather than a woman and a man, you have the same problem. You give the same message: the trauma suffered by one person is meaningless unless it propels another person’s story.

In Marauders #22, Lourdes Chantel (who has been in the refrigerator for over thirty years) crosses the stage for the sole purpose of revealing her trauma to the protagonist, so that her pain becomes a fulcrum for the change undergone by the only real person in the story.

And that’s without considering the other damage such plots inflict, on characters and readers, by removing true agency from the protagonist. If a person is forced to change, by circumstances, they have no agency because they did not decide to change.

I think that’s about enough, don’t you? I’ve spent a week on this and my friends are sick of hearing about it. My thesis, I suppose, is that a requirement for good writing is that every character should be treated like a character, rather than a plot. And writers should be aware of the tropes that they’re using, as well as the reasons that those tropes appeal to them. Characters, like people, should be allowed to own their own traumas — you get better stories that way — and part of this process of self awareness requires writers to examine their own prejudices. Finally, switching the genders of the characters within a trope does not dismantle it, or render it any less toxic.

Happy reading.

Poet, novelist, fencer, pirate, Za-Za, and Comic Watch regular contributor Bethany Pope lives in China. They also hold an MA and PhD in creative writing. Their latest novel, The Hungry and the Lost, goes on sale December 1, 2021 from Parthian Books. You can follow them on Twitter at @theMasqueWriter.